Data Insights: How the Pandemic is Affecting the 2020-2021 School Year

Data Insights: How the Pandemic is Affecting the 2020-2021 School Year

The Ohio Department of Education aims to provide schools and districts with the most effective supports and resources so they can continually improve to be the best they can be for each child. During times of change and pandemic-related uncertainties, reliable information and quality supports are more important than ever. Districts and schools are using real-time data and information to inform student-centric decision-making and action taking and fuel school or district improvement. Data also is key to unlocking many pieces of the equity puzzle. State-level data can provide insight into statewide trends and phenomena that can help inform state policymaking and action.

The following information highlights state-level data points. As is best practice in continuous improvement science, the Department encourages schools and districts to constantly consider effective ways to collect, analyze and make sense of their data and use it to set goals and drive improvement.

Several

key themes emerge from early data about the 2020-2021 school year:

- Education Delivery Models: From early September through early November, more school districts offered in-person learning than remote or hybrid learning. That changed in mid-November when more districts began relying on remote or hybrid learning.

- Internet Connectivity and Technology Needs: In some cases, a student’s opportunity to learn has been hampered by limited access to internet connectivity and technology devices.

- Student Enrollment: Total enrollment in preK-12 public schools decreased by 53,000 students—or 3%—between fall 2019 and fall 2020. By comparison, decreases in the prior three years ranged from 0.03% to 0.4%.

- Community school e-school enrollment grew by just more than 50% (approximately 13,000 more students).

- Student Attendance: Ohio does not yet have statewide data on attendance, although local data indicates that, in some cases, chronic absenteeism is a continuing concern.

- Fall Assessments:

- Test taking. The vast majority of eligible students took the fall Kindergarten Readiness Assessment (KRA) and third grade English language arts tests, but many of the state’s most vulnerable students did not.

- Lower scores. Scores generally are lower than past years, especially for Black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students.

- Remote education models. The decrease in the rate of fall third grade proficiency generally was more marked among students learning in districts using a fully remote education delivery model.

- Equity Implications. These preliminary data suggest the state’s most vulnerable students generally also have been the most affected. Local data should help tell a more nuanced story about these impacts and inform decisions about addressing the needs of each child.

As schools and districts continue to address recovery needs and learning lag, it is critical that available funding sources are prioritized to support that work. The federal government recently awarded Ohio schools and districts additional funding under the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund. This grant provides districts short-term resources that can be used for extended learning opportunities. To assist in this effort, the Department will continue to develop its collection of online informational resources while creating and leveraging key partnerships that can contribute to school and student success.

Understanding Opportunity to Learn

The pandemic ushered in a set of challenging learning conditions across Ohio, the nation and the world. These disruptions affected, in many cases, a student’s

opportunity to learn. Opportunity to learn refers to a student’s ready access to regularly offered educational opportunities—even in the most challenging of circumstances. Data points that gauge opportunity to learn might include types of instructional models used by schools and districts to deliver education, internet and technology device access, conditions of learning, attendance and engagement policies and other important factors that affect student success. The following data help paint a state-level picture of student opportunity to learn in Ohio.

Education Delivery Models

This section was updated April 26, 2021.

Education delivery models—that is, the mode in which schools and districts deliver instruction to students—have varied and changed over the course of the pandemic. In general, schools and districts use an education delivery model that is five-day in-person, fully remote, or hybrid (for example, two-days in-person and three-days remote). Model snapshots are updated weekly and can be found on the Department’s Reset and Restart Education webpage.

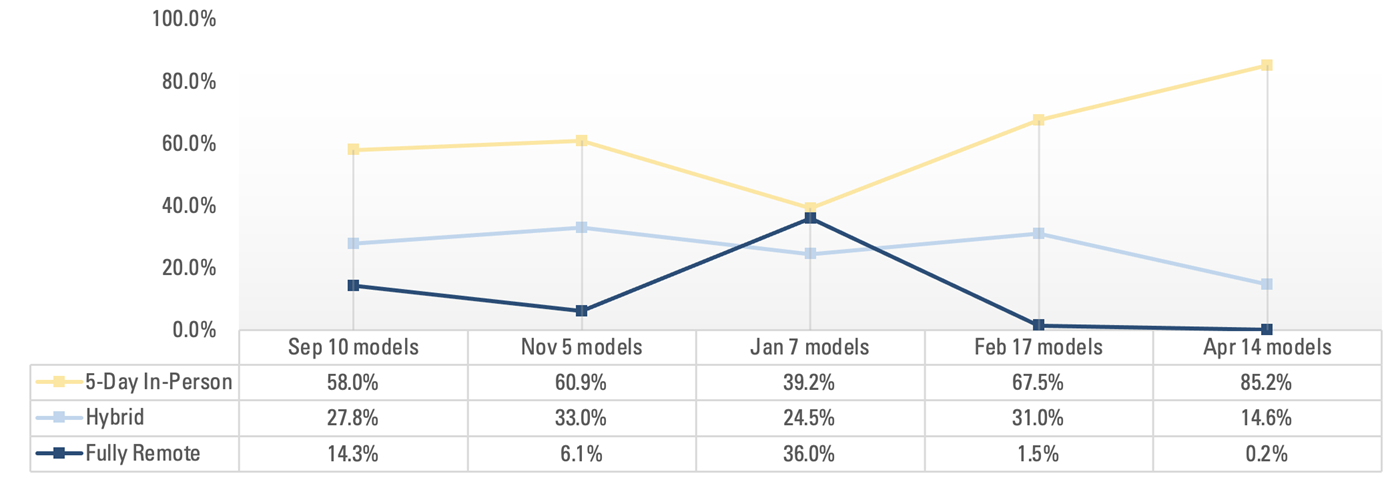

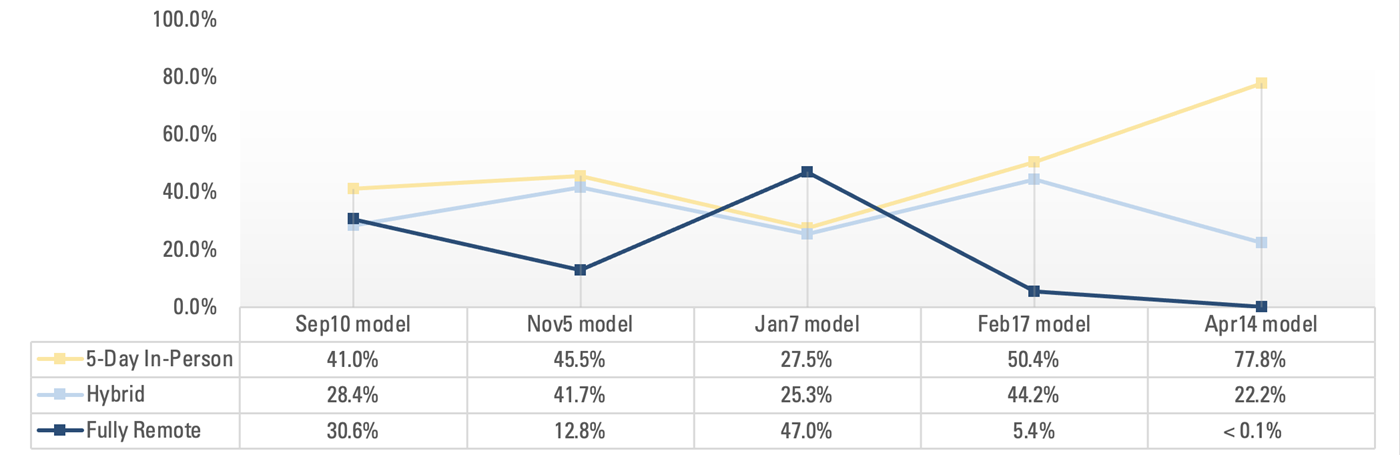

The 2020-2021 school year has been characterized by four trend periods (see Figures 1 and 2 for corresponding data):

- Early Fall: From the beginning of the academic year through early November, there was a slight rise in the number of districts using five day in-person and hybrid models, with a corresponding decrease in districts using a fully remote model.

- Late Fall: The early fall trend was followed by a sharp increase in fully remote models from mid-November through December, peaking at 219 districts, with nearly half (47%) of traditional school students enrolled in a fully remote district on Jan. 7.

- Winter: The number of districts offering in-person learning, through five-day in-person or hybrid models rose quickly at the start of 2021. Less than 10 districts were still fully remote by February 17 .

- Early Spring: By mid-April, only one district continued in a fully remote model. The remaining districts have steadily transitioned to five-day in-person models, such that 519 districts are entirely in-person, covering over three-fourths (77%) of all traditional public school students.

Figure 1: Percent of 609 Traditional Public Districts by Education Delivery Model (five selected snapshot dates)

Figure 2. Percent of Traditional Public School Students by Education Delivery Model of District

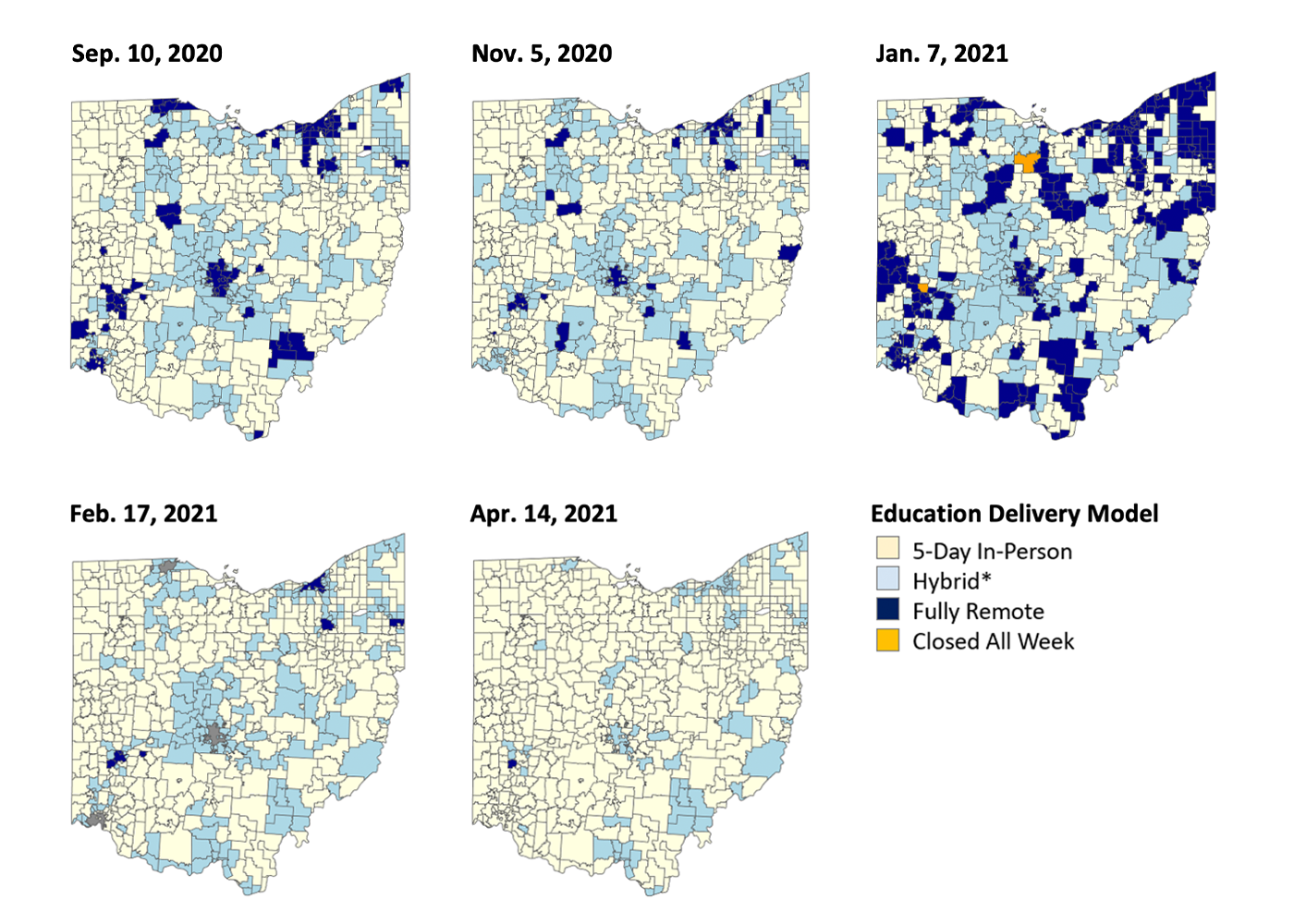

Figure 3 displays the distribution of model types across the regions of the state for the same five snapshot dates in Figures 1 and 2. In general, the urban and more densely populated districts have represented a large portion of those districts using fully Remote or hybrid models.

Figure 3. Education Delivery Models (five selected snapshot dates)

*In mid-February 2021, the Department began distinguishing between two types of hybrid models. Full access to hybrid means that every student has the option to attend at least some in-person classes. Partial access to hybrid, means that only some students have access to in-person classes (usually determined by grade level). Since mid-February 2021, no more than five districts used the partial access to hybrid category (displayed in gray on the Feb. 17 map). For the purposes of this Data Insights analysis, hybrid is a single category.

Internet Connectivity and Technology Needs

In a variety of situations, students’ opportunities to learn have been hampered by limited access to internet connectivity and technology devices. In spring 2020, internet connectivity and technology-device access stood as one of the top three challenges districts, educators and students faced as Ohio shifted to remote education.

1 This need persisted significantly into the 2020-2021 school year. The reasons for the need can vary. In some cases, families do not have internet access in their homes or they do not have the technology devices (such as laptops or tablets) necessary for their students to connect to the internet. In addition, large regions of Ohio do not have the necessary infrastructure to support widespread internet access.

A sample of Remote Learning Plans submitted by school districts in August 2020 noted the following:

- Forty-five percent of districts were working to increase students’ in-home internet connectivity, while 30% of plans reflected work on increasing community options for internet connectivity (for example, access to free Wi-Fi in school parking lots).

- A much higher percentage of districts (85%) described plans to provide technology (such as laptops or tablets) to students.

- Forty-three percent of districts planned to increase both connectivity and technology access.

These findings align to results of the American Community Survey (2018), which found that one in six Ohio households lacked a broadband connection and one in eight had no internet access.

To help schools and districts address internet connectivity and technology device access issues, the Department, working in conjunction with a set of public-private partners, launched

RemoteEDx. This suite of tools, aimed at enhancing remote education opportunities, includes the

Connectivity Champions, which offer schools and districts boots-on-the-ground support to overcome barriers to internet connectivity and technology devices. The Connectivity Champions helped schools and districts link to and maximize use of a

$50,000,000 BroadbandOhio Connectivity Grant aimed at immediately expanding broadband services across Ohio.

Student Enrollment

Student enrollment changed in exceptional ways during the 2020-2021 school year. Parents and families faced tough decisions about the best options for their students’ education, health and well-being. Parents and families, in many cases, wrestled with questions surrounding enrolling their students in preschool or kindergarten and the education delivery model (remote education; in-person learning, if offered; or home-schooling) that would best meet their students’ needs. While statewide enrollment data cannot speak directly to why families made the decisions they did, it can shed light on what happened.

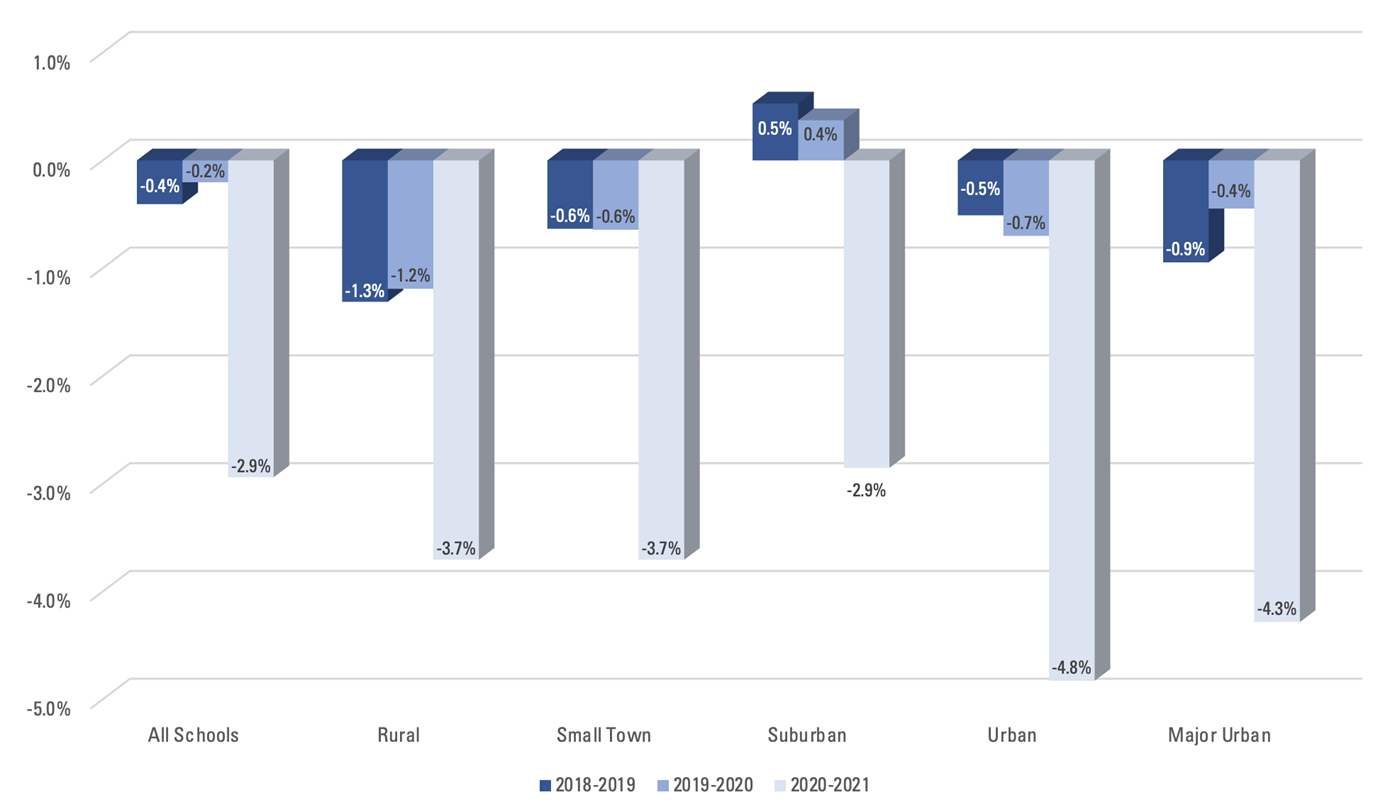

- Total enrollment in preK-grade 12 public schools decreased by 53,000 students—or 3%—between fall 2019 and fall 2020. By comparison, decreases in the prior three years ranged from 0.03% to 0.4%.

- More than 90% of Ohio’s districts experienced decreases in enrollment, ranging from less than 1% to more than 15%.

Digging deeper into the statewide data provides greater nuance relative to the overall decrease:

- Urban and major urban districts saw the greatest percentage change in enrollment at 4.8% and 4.3% respectively (this translates to roughly 9,800 fewer students in urban districts and 8,000 fewer students in major urban districts2) (Table 1). That said, students in suburban districts represent the largest share of the overall decrease in preK-12 enrollment.

- Roughly 30% of the absolute decrease in enrollment occurred in suburban districts, followed by just over 20% in small towns (approximately 16,000 and 13,000 fewer students respectively). Based on the distribution of students across district typology, it makes sense, then, that white students make up 90% of the decrease in overall enrollment (approximately 47,000 fewer students).

Table 1. Enrollment Decreased Across All District Typologies in 2020-2021

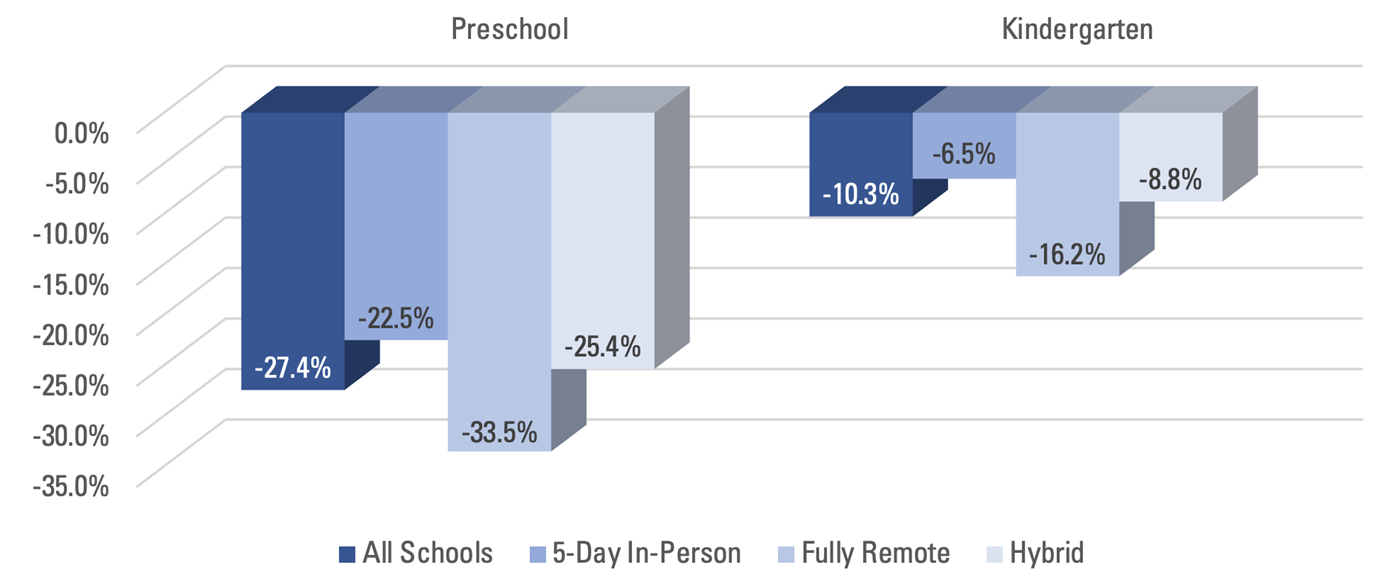

- Enrollment decreases are more concentrated in preschool and kindergarten. Between fall 2019 and fall 2020, enrollment in public preschools decreased by 27% (approximately 15,000 fewer students in fall 2020), while enrollment in kindergarten decreased by 8% (approximately 10,000 fewer students in fall 2020). These decreases represent almost half of the total decrease in enrollment across all grade levels. This reverses a two-year trend whereby public preschool and kindergarten grew by an average of 5% (or roughly 2,000 more students) and 2% (or roughly 700 more students), respectively.

- Enrollment decreases in preschool and kindergarten are especially pronounced in districts that began the school year fully remote (33.5% and 16.2%, respectively), compared to five-day in-person and hybrid education delivery models (Table 2).

Table 2. Among all public districts, preschool and kindergarten enrollment is down in 2020-2021. The decrease is greatest among those districts that began the year fully remote.

- Significantly, there are two education sectors that grew based on fall enrollment data.

- Home School: Based on preliminary data, Ohio’s home-school participation grew by approximately 25% (approximately 5,000 more students) between fall 2019 and fall 2020.

- Community School E-Schools: Community school e-school enrollment grew by just more than 50% (approximately 13,000 more students) between fall 2019 and fall 2020 (Table 3). In contrast to traditional public schools, the greatest increase in enrollment in e-schools was in early grades. Kindergarten enrollment in Ohio’s e-schools grew by more than 250% between fall 2019 and fall 2020 (approximately 2,200 more students); enrollment grew by more than 100% in every grade between first and fifth grade (an average of 1,300 more students per grade). Additionally, Black students represent a much larger share of the increase in community e-school enrollment (19%) than they do the decrease in overall student enrollment (9%).

Table 3. At the same time that overall enrollment decreased in 2020-2021, enrollment in Ohio's e-schools increased substantially.

It is hard to know with certainty what each of these data points reflects about the educational choices families are making or the pandemic-related barriers they face. Taken together, however, the data captures two separate concerns. The first: concerns about the feasibility and quality of remote education, which might have driven some families to opt out of, or delay entry into, public education altogether. If families had the flexibility to do so, some likely decided to hold off on preschool or kindergarten one more year, opting to home school instead. The second concern: questions about the safety of in-person learning during a pandemic, which might be another cause for increases in home school and in community school e-school enrollment.

The

full enrollment report contains data for all Ohio school districts.

Student Attendance

Enrollment data does not speak to

attendance, one of the most significant factors contributing to student success. Barriers to attendance look different during the 2020-2021 school year and may be more significant for some students than in the past. Ohio’s most underserved students likely have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, increasing their risk of absences. Now more than ever, it is important for districts and schools to work with students, families and partners to identify approaches for encouraging and tracking attendance that accommodates the unique situations of each child.

Ohio is moving to collect targeted statewide data that will shine a brighter light on how the pandemic is affecting student attendance. In the meantime, the Department continues to work with its

Stay in the Game! Network partners — the Cleveland Browns Foundation, Proving Ground and AttendanceWorks — to understand and support attendance. Local-level data collected through this partnership (which includes 10 school districts) offers some insight into what might be happening across the state.

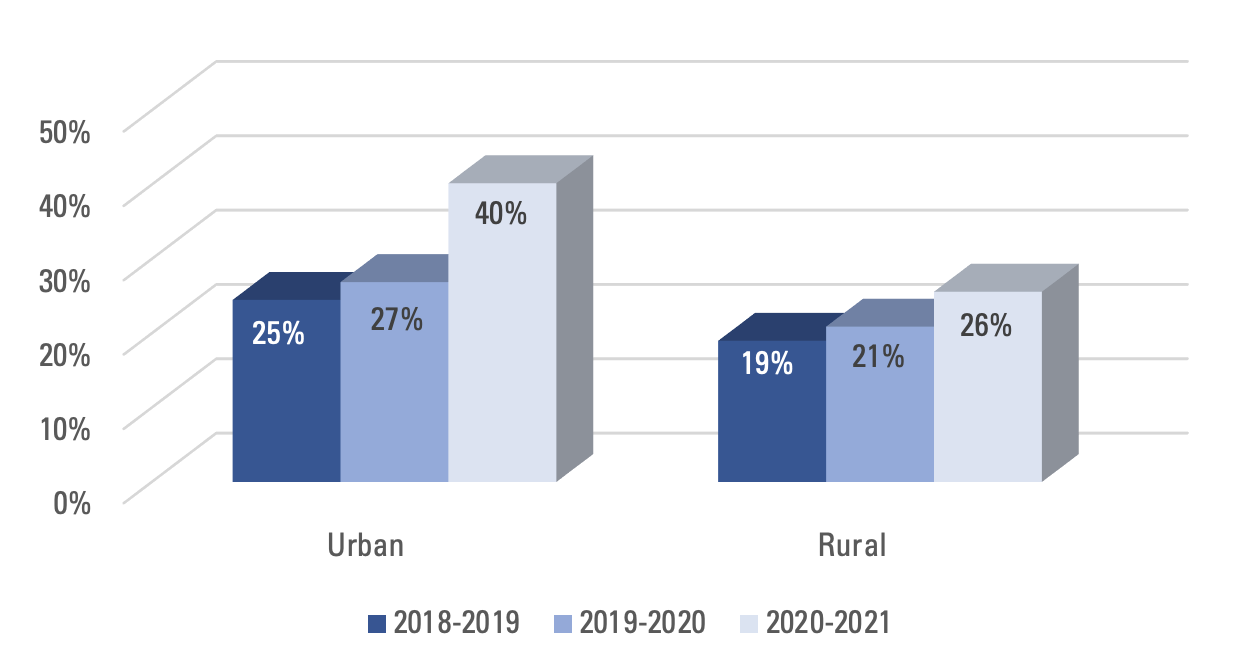

- Though the increase is smaller among rural districts, chronic absenteeism in the 2020-2021 school year is increasing notably in both urban and rural Proving Ground partner districts (Table 4).

Table 4. Among both urban and rural Proving Ground partners, chronic absenteeism is up.

- Students who were chronically absent (missing 10 percent or more of the school year for any reason) before the pandemic face a new set of attendance-related barriers; their likelihood of being absent has increased.

- Chronic absenteeism is increasing across all grade levels. Among urban districts participating in Proving Ground, the increase is largest within elementary schools (Table 5). Chronic absenteeism rates did not increase as quickly among elementary schools in rural districts. In rural districts, elementary students were more likely to engage in in-person learning during the fall of 2020-2021.

| Table 5. Among Proving Ground's urban partners, chronic absenteeism in elementary schools looked similar to other schools in 2020-2021. |

| |

2019-2020 |

2020-2021 |

Change |

| Elementary School |

19% |

35% |

16% |

| Middle School |

25% |

36% |

11% |

| High School |

40% |

51% |

11% |

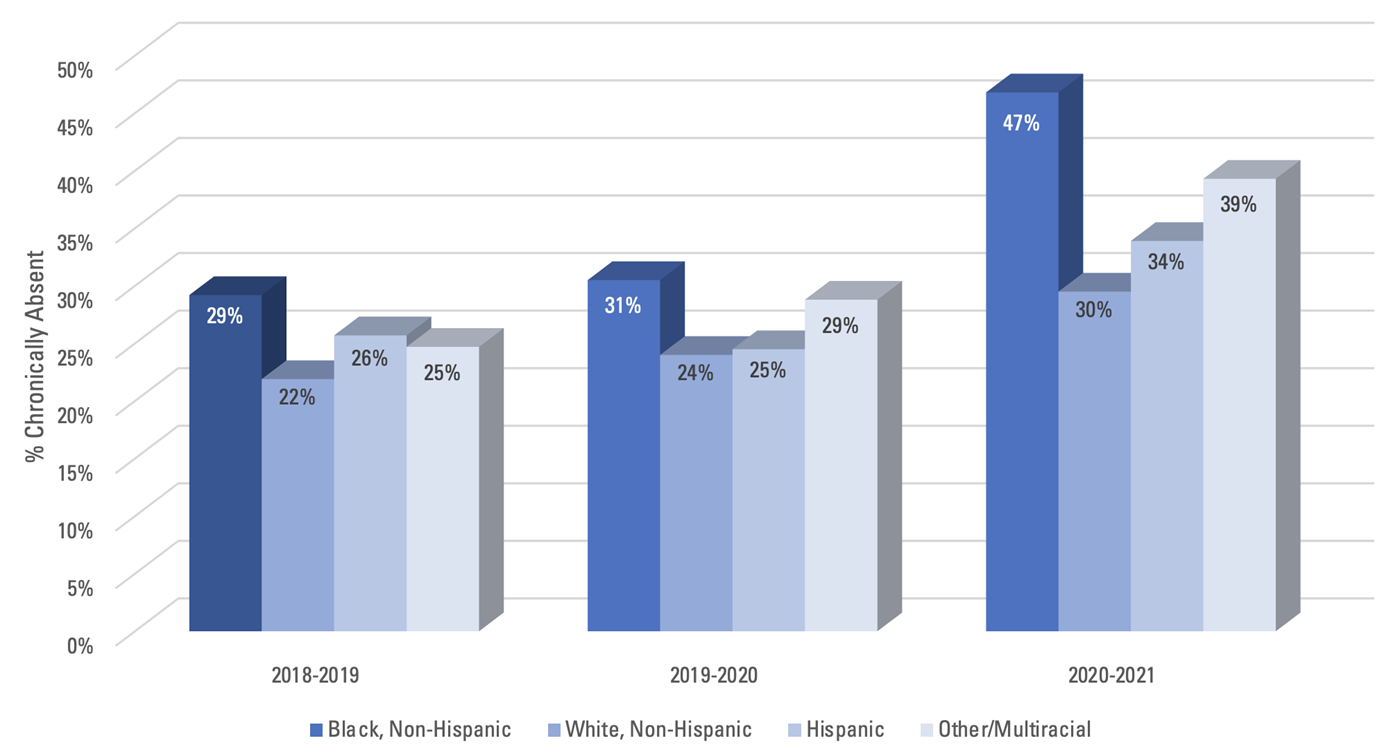

- The attendance gap is widening. Chronic absenteeism rates for Black students generally always have been higher than for other students; however, in urban districts, Black students’ chronic absenteeism rates were substantially higher in the fall of 2020-2021 compared to other students (Table 6).

Table 6. Among Proving Ground partners, gaps in chronic absenteeism increased in 2020-2021a

aFor all years, chronic absenteeism rates reflect data from start of school year through January 25.

aFor all years, chronic absenteeism rates reflect data from start of school year through January 25.

Fall Assessments

Results from Ohio’s 2020 Kindergarten Readiness Assessment (KRA) and fall third grade English language arts assessment represent the first statewide assessment results since the start of the pandemic. The Department has conducted a preliminary analysis that includes participation, state-level results, district-level results and subgroup performance. This section highlights the results of these assessments and their implications in light of the pandemic’s impact on student learning.

It is important to emphasize how these results should and should not be used. These data provide some clues to generally understanding where students are in their progress. Different groups of students may be in different places. The preliminary participation and assessment data suggest the state’s most vulnerable students have been most impacted.

These preliminary data can be used to support continuous improvement purposes to inform instructional and policy decisions. Educators can use the data in conjunction with other local sources of data (such as formative assessments, school climate surveys and attendance data) to address the needs of each child.

It is important to note these data should not be used to rank districts and should not be compared to previous Ohio School Report Card results.

National Trends

A growing body of national research focuses on understanding the pandemic’s impact on student learning.

3 Studies have identified areas of learning lag, which can more significantly affect vulnerable student populations. This could be further complicated because vulnerable student populations might be underrepresented due to lack of test participation (for example, students in fully remote education districts).

Preliminary findings from studies by both

NWEA involving schools using the NWEA suite of assessments and of districts using

i-Ready assessment tools suggest the pandemic has created greater gaps in learning for math than reading. The impact appears to be more significant among Black students and students of color, widening an already existing achievement gap. A study from

Amplify, using DIBELS® assessment data, identified learning lags in phonemic awareness, which is a critical skill in learning to read. This likely will lengthen the amount of time it takes young learners to reach preliteracy milestones.

Child Trends explored the impacts on young students with disabilities, including loss of in-person therapy time, limited access to special education accommodations and adapted materials. These circumstances are likely to directly affect the ability of students with disabilities to access both general education and specially designed instruction necessary to meet their learning needs.

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment (KRA)

Since fall 2014, kindergarten teachers have administered the KRA at the beginning of each year. In fall 2020, a shortened form of the KRA (known as the KRA-R) was administered statewide. While some of the items could be administered using video or remote platforms, the KRA-R required students to take the assessment in person. A preliminary report on the

statewide fall 2020 administration is available.

Fall Third Grade English Language Arts Test

The third grade English language arts test measures student proficiency on the grade 3 Ohio’s Learning Standards for English language arts. The fall test is an early marker of student performance on those standards. Students have another opportunity to take this test in the spring. Researchers from the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University conducted an analysis of the fall English language arts data, comparing participation and performance to that from the 2019-2020 school year. The full report is available on the

John Glenn College of Public Affairs website.

Common Themes in Preliminary Statewide Results

Key themes emerge across both the KRA and third grade English language arts fall assessment. The data show the following:

- Test Taking: The vast majority of eligible students took the fall tests, but many of the state’s most vulnerable students did not.

- Seventy-eight percent of enrolled kindergarten students completed the KRA (compared to 93% last year). The students who did not were more likely to be students with disabilities, English learners, economically disadvantaged or non-white.

- More than 81% of third-grade students took the third grade English language arts test (compared to 95% last year). The students who did not were more likely to be minority, economically disadvantaged and/or reside in districts with low average achievement levels.

- The Department offered practical advice to districts by emphasizing that first and foremost they should be attentive to the safety of students and staff. In addition, flexibility was provided for testing. Districts made good faith efforts to complete testing, but districts using a fully remote education delivery model faced logistical challenges in completing assessments, which could not be administered remotely.

- Lower Scores: Overall scores are notably lower than past years, especially for Black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students.

- Using the Language and Literacy domain of the KRA-R, 47.6% of the participating students scored not on track, significantly more than in 2019 (39.7%), 2018 (39.1%) or 2017 (38.3%).

- A higher percentage of children taking the KRA-R scored in the lowest performance level, Emerging Readiness, than in any previous year (23.7% compared to 22.5% in 2019, 22.7% in 2018 and 22.4% in 2017).

- Fall 2020 third grade proficiency rates are approximately 8 percentage points lower than in 2019 (37.1% in fall 2020 compared to 45.1% in fall 2019).

- More than 87% of districts had a decrease in their percent of students scoring proficient or higher from 2019 to 2020. The average decrease in students scoring proficient or above was slightly more than 9%. This included decreases in students scoring in Advanced, Accelerated and Proficient performance levels; with an increase of students scoring in the Basic and Limited range.

- Remote Education: The decrease in third grade proficiency was more marked among students learning in districts that used a fully remote education model as their primary education delivery model in fall 2020. In fully remote districts, fall third grade proficiency rates decreased by approximately 12 percentage points, compared to decreases of approximately 8 percentage points in districts primarily using a five-day in-person model and 9 percentage points in districts primarily using a hybrid model.

- Equity Implications: This preliminary participation and results data highlights the impact events of the past year have had on Ohio’s most vulnerable students. For example:

- While participation rates on the fall 2020 third grade English language arts test decreased by 14 percentage points overall, the decrease was more pronounced for Black, Hispanic and Asian American students compared to white students (percentage point decreases of approximately 29, 18, 14 and 10, respectively). Participation rates for economically disadvantaged students decreased by 19 percentage points, compared to 8 percentage points for non-economically disadvantaged students.

- At the same time, the decrease in fall 2020 third grade proficiency rates also was more pronounced among Black and Hispanic students compared to White and Asian American students (a 12 and 10 percentage point decrease, compared to 7 and 8 percentage point decreases, respectively).

Additional data collected at the local level may provide more insight into how students have been impacted. It also may help inform local decisions about ways to address the needs of each child.

District-Level Data Files

Districts have received detailed information regarding these assessments, which can be used to drive improvement conversations at the local level.

More details on each district are available in the following files:

District KRA-R and

District ELA .

Note: These data represent preliminary data from test vendor files that have not been verified through the EMIS submission process. This information should not be considered final and is not comparable to previous Ohio School Report Cards.

Using These Data to Support Students

While the data from early assessments show declines in performance trends, especially for vulnerable groups of students, the focus should be on how to best support students. Test data is one important piece of information but not the only information that should be considered. Schools and educators have access to multiple sources of information that should inform their instructional strategies, student support approaches and decision-making. Districts are encouraged to use these data within the Ohio Improvement Process or another similar continuous improvement process.

Practical Step-by-Step Processes for Using These Data

Based on best practices, schools and districts can take the following actions to develop and implement plans for supporting Ohio’s youngest learners during the 2020-2021 school year. Schools and districts should use all available data and knowledge of student conditions to inform their work.

Bring the Community Together to Identify Concerns and Implement Actions

- District and school personnel should start by identifying areas of focus and concern. Do the data show learning lags (by subject? by grade?) for all students or specific student groups? Are these data different than other years? Examine the district or school’s multi-tiered system of support framework. Based on the data, are 80% or more of the students at or above expectations or benchmarks at a specific grade level. If not, examine instructional strategies and materials used to support all students in Tier 1 instruction. It is important to bolster Tier 1 instruction to ensure intervention services are not being overburdened. Examine student progress monitoring data for students accessing Tier 2 and more intensive Tier 3 intervention supports to determine if those supports are accelerating student outcomes. To what extent do school personnel report being connected to their students such that they understand what each child needs?

- Bring together key partners within and outside of the district and school. Discuss what each participant is seeing in the community, the data and areas of concern and decide on areas of focus. Partners could include community child care providers, funders, business, philanthropy, local library administrators, preschool home visiting programs, district administrators, early grade teachers, literacy-focused experts and state support team and educational service center representatives.

- Together, develop a plan to address learning lags:

- Identify the implementation components and outline an action plan that includes:

- A timeline;

- Key personnel;

- Resources and supports for child care providers supporting preschool/rising kindergarten and kindergarten-grade 3 students.

- Specifics of implementation:

- Student opportunities for instruction, extended learning opportunities, engagement and learning that could be planned for the spring, summer or before the academic year begins in 2021;

- Professional development for specific instructional strategies;

- Coaching grade-level teams;

- Systems structures, including leadership supports, grade-level supports and teacher supports.

- Measures of success:

- Establish a process for monitoring progress and implementation of the plan’s strategies.

- Review the available resources the Department has provided on supporting students.

- Review what national studies are finding (summarized and linked above).

- Establish a communication plan for families of young learners. Some questions to consider include:

- What message is being communicated to families about supporting their learners?

- How were fall assessment results communicated?

- What opportunities are there in the community, school and at home to support learning?

- Develop a basic message for families and caregivers to explain assessment results. Ensure teachers understand how to explain results and concrete actions families can take to support their young learners.

- Host regular meetings with the partners to check on activities and progress.

Using the Data to Inform Needed Supports

In addition to the KRA-R and fall third grade English language arts data, other related data may be useful in planning supports for students, including:

- Alternate Assessment for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities.

- K-3 reading screening (referred to as “Reading Diagnostic Assessments” in the Third Grade Reading Guarantee).

- Progress monitoring data for students receiving interventions under Reading Improvement and Monitoring Plans.

- Other formative assessments.

The KRA-R is a

screening assessment. It assesses four areas of early learning:

- Social foundations;

- Mathematics;

- Language and literacy; and

- Physical well-being and motor development.

- For students with overall scores in the Emerging Readiness and Approaching Readiness categories, additional follow up or support is recommended.

- The language and literacy portion of the KRA-R can be used to meet the reading diagnostic requirement of the Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Students’ language and literacy domain scores can be considered and compared to determine next steps for groups of students.

- Strengths in language and literacy domain scores can provide some information to consider regarding language and literacy instruction in preK programs.

- Individual student scores can determine areas of strength and need that can inform instruction, as well as indicate areas where additional data is needed.

Guiding Questions for KRA-R Data Review

- Which students are in the Emerging Readiness category? What schools are they in and what supports are offered to their teachers?

- Are there particular schools or classes with a larger number of students in Emerging Readiness? How about Approaching Readiness?

- How does the performance of each student group compare to the overall data? If applicable, how do individual schools compare?

- How do the scores of students in student groups compare to the overall population?

- What skills were most students able to demonstrate? What skills stand out as areas where students need support?

- Which students are outliers in a specific domain and require differentiated instruction or enrichment?

Administrators Asked: We completed the KRA in fall 2020, but we are concerned our kindergarten students have not made typical progress due to remote or hybrid learning. What data can we use to measure our kindergarten students’ reading progress this year and plan for instruction?

An efficient way to measure young learners’ reading progress is through curriculum-based measurements (CBMs). CBMs are screening and progress monitoring assessments. They are used to determine mastery of specific skills or content and allow teachers to assess individual student’s responsiveness to instruction. CBMs generally consist of short (about one minute) probes that measure specific early literacy skills. At the middle and end of kindergarten, the district or school may want to consider using curriculum-based measures that assess print concepts, phonemic awareness, letter knowledge (sounds and names) and beginning phonics. This information will give the district or school more information on overall kindergarten literacy progress and can help teachers plan for instruction. If intervention is needed, teachers are encouraged to use further diagnostic assessments to plan for individualized intervention. This does not necessarily mean the student receives 1:1 service but the student’s individual needs are planned for when designing the intervention. Diagnostic assessments might consist of informal diagnostics, such as a phonemic awareness or phonics survey, or more formal diagnostics requiring support from trained professionals.

The third grade English language arts assessment is an

outcome assessment, which can help answer the questions:

- Were goals for students and systems achieved?

- Did the instruction provided work and, if so, for whom?

The goal of outcome assessments is to know if grade-level expectations have been met. It is important to note the state’s third grade English language arts assessment measures end-of-year third-grade expectations, even when administered in the fall.

Administrators Asked: What if our students’ performance on the fall 2020 third grade English language arts assessment is significantly below how our district or school’s students typically perform and this was unexpected given the students’ previous progress?

This may be an indication from the outcome assessment that students have experienced gaps in their learning from being out of school or receiving instruction remotely. The district or school can use this information, alongside locally collected data, to inform a district or school’s

learning acceleration plan. TNTP has developed a user-friendly

guide for planning for acceleration for the next two years. Three important concepts the guide points out include:

- “Accelerated learning and cultural, social and emotional responsiveness are not mutually exclusive: Learning doesn’t happen at the expense of responsive teaching, or vice-versa. The truth is that a core part of strong instruction is responding to the cultural, social and emotional needs of students. If instructional practices leave students feeling displaced, invisible or unsafe, accelerated learning can’t happen. Likewise, trauma-informed instruction and cultural, social and emotional responsiveness do not require forfeiting strong, grade-level-aligned instruction.

- Accelerated learning and strong instruction are interdependent: You can’t accelerate learning with poor instructional practices in place, and you can’t have strong instruction if you cannot effectively support unfinished learning. Therefore, it is important to develop your leaders and teachers on the concepts and best practices of accelerated learning and strong instruction.

- Accelerated learning and strong instruction should not cause further trauma: Educators have the potential to cause trauma. We can cause additional trauma to students by denying them access to a high-quality education, and we can cause trauma by putting systems and structures in place that prevent students from accessing high-quality instruction. We must consistently evaluate and understand the consequences that our instructional decisions have for the children we serve and the adults that support them” (TNTP, April 2020).

Resources for Schools Supporting Young Learners and their Families

Literacy intervention intensification may be needed for more children than in typical school years. While the district and school focus on ensuring each grade has a viable and guaranteed standards-aligned curriculum, teacher-based teams can plan for intensified intervention. As in a typical year, intervention still occurs

in addition to grade-level instruction. Teams may want to use the

Intervention Intensification Strategy Checklist from the

National Center on Intensive Intervention.

Resources for

literacy instruction within remote learning environments are available through the Department’s

Restart and Reset Education website. These resources include a white paper and videos describing evidence-based literacy instruction focused on teaching reading online, families as partners and new literacies (digital literacies), as well as a

K-Grade 5 Remote Literacy Planning and Discussion Guide. This guide focuses on the components of effective K-5 literacy instruction, addressing learning gaps and accelerating progress, partnering with families and caregivers, delivering instruction through multiple methods and training and coaching educators. The Department also continues to provide educator meetups on

Reading Interventions in a Digital Environment.

Child care providers play an important role in learning for younger children. Districts should consider reaching out to their communities to invite child care providers to the discussion and planning table. To search by zip code, county or other factors, use the

Ohio Child Care Search webpage to obtain contact information for nearby providers. Providers who work with young children have much to contribute about the experiences preschool children and their families have had during the pandemic. Early childhood teachers know the children who will be coming to kindergarten and have thought about strategies for supporting children while they attend child care or summer camp programs. Multiple resources have been created to bridge the child care-school partnership, including a suite of

resources from Head Start, the Pew Center on the States’

Pre-K Collaborations with Community-Based Partners and numerous resources for planning from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Families and caregivers play a critical role in accelerating learning for their children. The

National Center on Improving Literacy provides resources to support families as partners in remote literacy learning, beginning reading, screening, dyslexia, interventions and legislation. Parents and caregivers who may be interested in supplementing their children’s literacy instruction at home are encouraged to partner with their children’s teachers and consider using the activities from the Regional Educational Laboratory at Florida State University’s website,

Supporting Your Child’s Reading at Home. This website provides family activities with easy-to-follow instructions to help children practice foundational reading skills including short videos and tips to help families use the activities to help their children grow as readers. This resource is for kindergarten-grade 3 but may be appropriate for children receiving intervention in grades 4-5.

The Council of Chief State School Officers

created new resources to help schools and districts put its Considerations for Teaching & Learning guidance into practice. The resources are brief, topical summaries on specific topics, with links to help educators find more detailed guidance. The following are direct links to the new resources:

Other Resources

The Department has many other resources to support the use of data, including:

Additional information, relevant data and resources will be added to this page as it becomes available.

1 Based on a spring 2020 Education Management Information System (EMIS) survey administered to all traditional public districts, community schools and joint vocational school districts. The survey asked respondents to identify the top three challenges they faced in the shift to remote education. Seventy percent of respondents identified students’ connectivity access among their top three challenges, while more than half identified students’ technology access among their top three challenges.

2 The Department uses a

typology of districts to stratify districts for research purposes.

3 The inclusion of any article should not be considered an endorsement of the author(s), publication(s) or funder(s). Full text publications are linked, and any questions about the methodology, findings or suggested strategies should be directed to the authors.

Last Modified: 4/7/2025 7:35:21 AM